He's sophisticated in the distinctions he makes between different kinds of antisemitism on the Left - the 'primitive antisemitism' of wealthy Jewish banker stereotypes and 9/11 conspiracy theorists...the sort of thing that has permeated the left from aspects of the neo-anarchist tradition best represented by the Occupy movement, vs the "anti-imperialism of fools" variant that is a descendant of Stalinist perspectives on international struggles, with nations and states and movements all sorted neatly in goodies and baddies, so that if someone is against the United States then they must ultimately be on the side of the angels. He points out how these two threads came together in the Corbyn moment in the Labour Party. I think he rather tends to play down the extent to which some of the accusations about antisemitism were made in bad faith, as part of a factional struggle by people who didn't care much about Jews but wanted to get at the Left. That goes for Corbyn's enemies within the Labour Party and for some elements of the 'leadership' within the Jewish community.

Where I think the book disappoints is in its account of Zionism. Sure, Zionism functions as a "nationalism of the oppressed" for some diaspora Jews, and did even more so at times when Jews were a persecuted and endangered minority. And yes, Zionism is now bound up with the personal identity of many diaspora Jews who half-imagine themselves as a sort of expatriate Israeli, so that they think of Israeli culture as their culture. But still, I don't think it's right to treat Zionism as just the Jewish flavour of Eastern European nationalism, so that we hold the left to account for not treating it in the way that we treat other nationalisms.

Zionism was always a weird kind of nationalism. Other nationalisms were engaged with the folk culture of the nation that they claimed to represent - the songs, the dances, the language. But Zionism, very unusually, was utterly uninterested in the language/s that its constituencies actually spoke, or the songs that they sang, or their literatures. Instead it favoured a language and a culture that it made up - modern Ivrit is a creole of liturgical Hebrew, and the Zionist folk songs that I grew up with have tunes that are lifted from other cultures - Russian and Rumanian, for example. There is no sentimentality about the beautiful mountains and forests of the homeland, because the territory on which the Zionists sought to create their nation was not one with which they had anything except a historical and religious connection. And quite unusually, there's quite a lot of contempt for the actual members of the constituency, who are believed to have weak, submissive, ghetto-dweller characteristics. Again, this is not absolutely unique among nationalisms; I'd say that some of the currents in Black nationalism among African-Americans are sometimes like that.

In fact, as Randall notes elsewhere, Zionism has/had lots in common with Garveyism. The latter rightly attracted a lot of hostility from African-American socialists and communists, and it's possible to imagine another world in which hostility to Zionism as reactionary and utopian might have stayed like that, rather than shifting into the full "anti-imperialism of fools" that it did.

Perhaps in that world the Zionist settlements in Palestine might have ended up like the German Templar colonies (also in Palestine), a quirky blind alley of history with a few thousand (or perhaps tens of thousand) inhabitants, funny little communities in an independent, post-colonial multi-confessional Palestine.

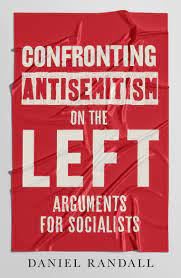

None of this really distracts from the value of the book, which is about antisemitism rather than about the politics of Israel and Palestine. I'm going to recommend it to all of my friends, especially my friends who are engaged in active or passive solidarity with the Palestinians, and see what they make of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment